The APPS Act and how it will impact your privacy

The bill has several goals in terms of data privacy:

- Prior to collecting the data, the application shall “provide the user with notice of the terms and conditions governing collection, use and storage of personal data…” §2(a)(1)(A)

- Obtain consent from the user – §2(a)(1)(B)

The developer would be required to disclose the following:

- Categories of personal data to be collected – §2(a)(2)(A)

- Categories of purposes the data will be used – §2(a)(2)(B)

- Categories of third parties which the data will be shared – §2(a)(2)(C)

- The data retention policy governing the length personal data will be stored and terms and conditions of the data storage – §2(a)(2)(D)

What does this mean for users?

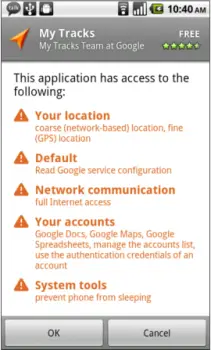

Now to dispense with the legalese and talk about what this means in plain English. Currently the Play Store discloses a fraction of this information. Let’s take the image of the permissions for an app above. As you may note, the app indicates that it will have access to (1) GPS (ie – your location); (2) it can read your Google service configuration; (3) it has full internet access; (4) it has access to your Google accounts and authentication credentials; and (5) it can prevent the phone from sleeping. This type of disclosure would certainly violate the APPS Act.

How would a disclosure that was in conformity with the APPS Act look? Let’s again use the permissions image and specifically look at the location services disclosure. The categories to be collected are relatively straight forward, and this app would likely meet the requirements in terms of “personal data to be collected.” Perhaps plain language would be used instead of technical language. An example may be, instead of stating “course (network-based) location, fine (GPS) location” the app might say something like “this application will track your location based on GPS and cellular data.” However, the Act would require further disclosure. The developer would have to disclose why the data is being collected, who will be using the data, the length of time the data will be stored and how the data will be stored. As you can imagine, this might require the user to scroll through pages of information in order to install the app.

Users will absolutely benefit from the required disclosures in the proposed Act. However, most significant to the security minded folk may be subsection (b). Subsection (b) of the APPS Act concerns “Withdrawal of Consent.” The Act would require developers to provide a means for users to inform the developer of their intent to stop using the app and request the developer “refrain from any further collection of personal data through the application” and at the user’s request, either “delete any personal data collected by the application that is stored by the developer” or “refrain from any further use or sharing of such data.” §2(b)(1)(A)-(B).

Rep. Hank Johnson (D-GA)

What does this mean for developers?

Now that the main points of the Act regarding users have been discussed, let’s discuss for a moment how this will affect developers. Section 3 of the Act concerns enforcement of Section 2 provisions. The Act delegates enforcement to the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”). The Act also gives a State’s Attorney General power to bring a civil suit on behalf of its citizens, should the State feel a developer is violating the Act. Lastly, the Act incorporates a “safe harbor” provision that allows developers to satisfy the requirements of the Act if they adopt a code of conduct for consumer data privacy.

In terms of the effects on developers, developers may be on the hook for violating the Act’s disclosure requirements. However, don’t jump to the recent CFAA news and the unfortunate case of Aaron Swartz as the potential punishment for violation of the Act. Nowhere, upon knowledge and belief, does the Act mention criminal punishment, only civil. Therefore, there will be no jail time and no federal criminal charges for developers who violate the disclosure requirements. Merely, the FTC or a State’s Attorney General could seek monetary damages against the developer. Maybe not a big deal to the likes of Google, but that prospect may be a cause for concern among smaller developers.

The FTC has also taken a proactive step by outlining recommendations for mobile application developers on its website. The recommendations basically track Rep. Johnson’s proposed legislation, laying out what developers should disclose to mobile application users. This step by the FTC will hopefully alleviate some of the burden on developers by encouraging developers to incorporate disclosures that will conform with the APPS Act before any law is passed by Congress. Those who would like to read the FTC’s full recommendations can take find them on the FTC’s website.

A move toward increased privacy

So, that’s the proposed Act. For the first time the United States government is attempting to regulate the collection and storage of mobile data in the name of consumer data privacy, a worthy cause to be sure.

From an end user prospective, does this adequately address privacy concerns? Some may be of the opinion that this will deter developers, especially those who release apps for no money. Might this Act stifle innovation among developers, or will compliance be relatively easy to incorporate into mobile applications?

This bill may not be perfect, but as the US government’s first meaningful step in addressing mobile data privacy concerns, how does it sound? Tell us your thoughts from consumer and developer points of view. For those who would like to follow this and other data privacy conversations, Rep. Johnson and many other experts (including myself, when I can) take part in the Twitter Chat #PrivChat on Tuesdays at 12 PM EST.